by Mick Cunningham & Dave Walsh

Professor David Whittaker

Professor David Whittaker

The twentysomething American woman sitting on my right is convinced that the O.J. Simpson murder trial in the States was the main turning point. I paraphrase, but it pushed the language of criminology into the vernacular, and audiences are now primed to view forensic science in drama form, hence primetime successes such as "CSI". Or maybe it was "Quincy". The thirtysomething woman sitting to my left likes "a good Patricia Cornwell" (novel), though her theory is that Ireland caught the forensics bug after the notorious "Kerry Babies" trial.

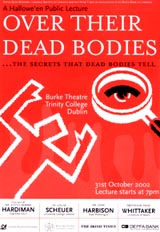

It’s Halloween, it’s Trinity College in Dublin, and we’re in a packed lecture hall (built in the late 1970s, official attendance 500) for an evening of public lectures entitled "Over Their Dead Bodies… The Secrets That Dead Bodies Tell". And dead bodies speak volumes.

The first speaker is David Whittaker, Professor of Forensic Dentistry at the University of Wales. He’s responsible for the standard text on forensic dentistry in the UK, and has been an expert witness for three decades throughout the UK for both the Crown Prosecution Service and the defence.

Crime fiction is so neat, but real life is often far more messy and interesting. Take, for example, that situation in a modern crime fiction where the detective trying to identify the dead body gets one of his/her subordinates to get somebody to search through the dental records. Sounds fine in theory, "do a check of the dental records", but in practice what do they do? Is there some kind of central dental records office, which has existed since time immemorial? And would this office really contain all the dental charts of all the nation? A dental equivalent of a national fingerprint database?

In practice it’s not like that. The likelihood is that you don’t have the dental records, so how does science fill in the gaps? All you might have is some teeth. In some cases such as a big fire, the teeth might literally be all you have of the body. They have "no biological turnover" and can survive intense infernos, forming a solid protection to encapsulate DNA. What stories do teeth tell? How can they be used to build up a profile of the individual regarding their age at death, sex and so on?

Leaving aside DNA analysis per se, Whittaker’s illustrated talk looked at two separate areas of forensic dentistry: the identification of unknown human remains from their teeth, and the analysis of bite marks. After a gory slide of an adult murder victim’s head, there was the microscopic view of a foetus’s minuscule tooth. Scientists can tell so much from a baby’s tooth – it can even indicate whether the child was born or not. Such is the trauma of birth that it creates a thin but unmistakable dark line, a dividing line in the tooth’s growth. (Perhaps it’s similar to how scientists look at the rings in prehistoric trees to check for whether a catastrophe such as a comet has created severe weather conditions.)

One of the lecture’s spookiest moments was when Whittaker touched on the investigation into the Fred West serial killings. Examination of the teeth of one of the bodies showed that it was a young girl of a particular age, and two of her front teeth had been crowned. The scientists analysed the crowning substance and found that these were temporary crowns. They then studied what bonding agent had been used between the tooth and the crown, to narrow it down to particular dentists. So they were now trying to identify a girl of a certain age who had disappeared shortly after receiving something like a sporting injury, had been given the temporary crowns by her dentist, and had been murdered before the more permanent crowns could be put in. By coincidence, one of the local police officers on the case said that while she herself had been at school, she had been in a hockey match where one of the girls had injured her two front teeth. The Fred West murder team followed it up and discovered that the injured hockey player at that very match had indeed been the victim.

Teeth can also be used as weapons, and bite marks are often seen in GBH cases, rape and murder. The marks can be on the victim or in inanimate objects (apples, chocolate, cheese etc). But the scientist starts from the evidence and the data, and then builds up the profile of what kind of suspect you would expect, not vice versa. "I don’t want to see a suspect first," Whittaker stressed, because this can introduce an element of bias – there is a natural inclination to try to fit the evidence around the suspect.

Comparing bite marks with an individual’s bite is a complicated business. Sure, any recovered DNA from deposited saliva may link victim and assailant. But bite marks are complex wounds and their interpretation requires knowledge of the biting mechanism and the changes that occur in injured tissue.

Among several amusing and slightly surreal anecdotes, Whitaker talked about how he had to investigate attacks by police dogs, in cases where the victims were seeking compensation. Some unscrupulous individuals would exaggerate the claim by getting the neighbour’s dog to add a few bite marks. So now there is a national database in England and Wales of the bites of police dogs.

Other areas covered by Professor Whittaker’s talk included techniques for reconstruction; photocomposition between teeth/skulls and photographs of the victim while alive; and computer-generated 3D models and VR.

– Mick Cunningham

Part II: Ireland’s

State Pathologist John Harbison »